All that is left is the art—the Aubusson tapestries, the Sèvres tureens.

When you pass into the courtyard of the Musée Nissim de Camondo, home to one of the world's most exquisite collections of 18th century objets d'art, what you notice first is a pair of marble plaques on the wall of the porte cochère. The first one is grand; unveiled when the place opened in 1936, it commemorates the museum's namesake, Nissim de Camondo, a young man of 25 who died fighting for France in the First World War and whose father Moïse donated the family's legendary collection to the nation in honor of his fallen son.

The second plaque is smaller, almost an afterthought. Added in the 1960s, it reveals that in 1944, eight years after the museum opened, Béatrice de Camondo, the founder's daughter, was deported to Auschwitz, where she, her husband Léon Reinach, and their two children, Fanny and Bertrand, were all murdered.

Today the Camondo dynasty no longer exists, its memory reduced to the silence of objects and things.

To visit the Musée Nissim de Camondo is to confront the haunting juxtaposition of arresting beauty and the incomprehensible rupture of the Shoah, the past that will not pass. The house, after all, is a temple of gilded abundance, a labyrinth of rooms showcasing the finest craftsmanship of France's "ancien régime"—Louis XVI chaises, ormolu clocks, and fanciful canvases by the likes of Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun and François-Hubert Drouais. But in equal measure it has become a somber meditation on the overwhelming absence of a family— and a world—that was brutally and systematically destroyed.

The Camondos, a Sephardic Jewish clan with roots all over the Mediterranean, were a decidedly European family at the proverbial end of Europe. Yes, the native continent of the Camondos would rebuild itself after the Second World War, but Europe's reconstruction has proven far from indestructible. The Brexit vote shook the foundations of the European Union, and a staggering number of voters, especially in France, are ready to follow suit in abandoning the enterprise.

As an increasingly powerful far right urges a return to the nationstate as a way of governing—and also of being—few in Europe today seem to remember the catastrophes that creeds of exclusion can engender. European history has somehow vanished, and it no longer seems fanciful to wonder whether in its absence disaster will strike again.

This is the power of the Musée Nissim de Camondo. It is a site of memory, a place that preserves with devastating intimacy the eternal darkness of the 20th century. Of course, many other memorials tell the story of the Shoah in its unfathomable immensity, but the Musée Nissim de Camondo, now a branch of Les Arts Décoratifs, is not exactly a memorial. It is the universe of one family, not of 6 million people, and its central question is whether it is ever possible to understand one's times.

Moïse de Camondo, after all, left all his worldly goods to the country he loved: the country his son died defending and the country that later sentenced his daughter to death. In ways that he would never understand, his collection evokes a striking fragility entirely unrelated to his delicate porcelain figurines or the Ming vases in the stairwell. In the end, the objects in the collection survived even though the family did not, proving far more durable than the world the Camondos thought they knew. Truth be told, that world never quite existed, and the mansion on the Rue de Monceau was always a refuge from an intolerable reality. But this we can say only in hindsight. And if we insist that the Camondos were victims of their own blindness, that they failed to understand their times, we have to ask whether we understand our own.

The Camondos were true cosmopolitans, at home everywhere equally but nowhere entirely. Their exact origins remain elusive, obscured by the vagaries of myth and memory. As Sephardic Jews, their ancestors were presumably among the masses expelled from Catholic Spain in 1492, only to settle across the Mediterranean world.

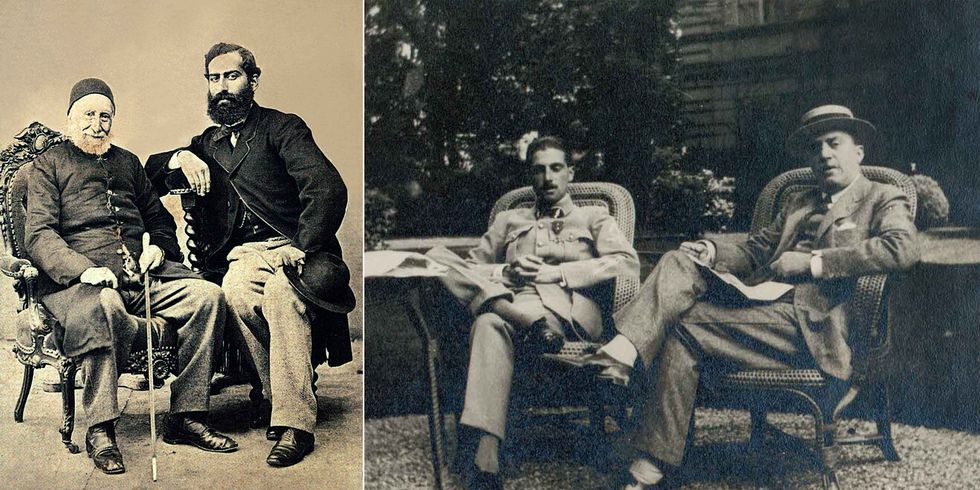

Some say their name came from the palazzo they occupied in Venice in the 17th century: the Ca' Mondo, the "house of the world." True or not, the Ca' Mondo story suits the family quite well, as there are surviving records of them trading in Trieste, Venice, Vienna, and elsewhere. Their principal home was eventually Constantinople, where, in the early 19th century, they became the most prominent Jewish banking family in the Levant, the socalled "Rothschilds of the East." But their citizenship was never Turkish: First they were Austrian, then they were subjects of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, and, finally, they were made counts of the Kingdom of Italy after that country's unification. Most accurately, the Camondos were citizens of the world, a clan for whom national boundaries were little more than imaginary lines.

In the wake of the Crimean War they moved to Paris, where they dazzled society with their wealth and, in the words of one cousin, a "flamboyant Italian title that sounded like that of a character in an Offenbach operetta." Flush with cash, subsequent generations reveled in the city's electricity, becoming fixtures at the opera and the storied Jockey Club. In the process they developed a certain reputation for outlandish expenditure. The novelist Emile Zola, for instance, later satirized their lavish compound on the Rue de Monceau as "a profusion, an explosion of riches," echoing the widespread impression of the family.

But in the France of the Dreyfus Affair, a 12-year social drama that elicited an unprecedented current of anti-Semitism, the Camondos—publicly prominent, exceedingly wealthy, and foreign-born—were eventually decried for their Jewishness as much as for their opulence. The anti-Semites of the age often attacked elite Jewish families like the Camondos for somehow "invading" France's cultural heritage, for buying houses and objects with aristocratic pedigrees that they, as foreigners, had no business owning. And if it was in the language of material things that prominent French Jews were often attacked, it was ultimately in the same language that many Jews would eventually respond. For no one was this truer than Moïse de Camondo; this was the drive behind his tireless passion.

To collect is to create. And what collectors primarily create is themselves. Whether they realize it or not, they see in the objects they pursue some aspect of themselves. Acquisition is almost always a means of self-recognition, and collecting a means of selfportraiture. This deeply psychological motivation has characterized almost every memorable depiction of collectors in literature, where collecting appears as a veritable disorder, especially in France's long 19th century. Balzac's Sylvain Pons, Proust's Charles Swann, and, most of all, Huysmans's Jean des Esseintes are all presented as victims of an insatiable affliction, the obsessive compulsion to possess.

But with possession comes a predilection for control, an obsession with the order of things. Few understood this better than the critic Walter Benjamin, himself an impassioned collector of books. "The most profound enchantment for the collector," he wrote in a 1931 essay, "is the locking of individual items within a magic circle in which they are fixed as the final thrill, the thrill of acquisition, passes over them." The "magic circle," it follows, is an alternate universe, a sanctuary into which a collector can retreat.

In his last will and testament, Moïse de Camondo wrote that his collection was meant to extol "the glories of France" in the "period I love above all others." That the 18th century was his chosen period should come as no surprise: The critics of his day proclaimed the decadent era before 1789 the pinnacle of French aesthetic grandeur, and most of the serious collectors of Moïse's generation pined for objects that, in their eyes, represented the last moment when France was really France.

In some ways, Moïse was among those collectors, but for him the objects he doggedly pursued represented far more than nostalgia for better days. Building one of the finest collections of ancien régime decorative arts was a way for a Jew from Constantinople to show an indisputable loyalty to France, his adopted homeland. Most important, it would show that he belonged. Yet this type of public presentation was Moïse's aim only after his death. In life, his project was to build a fortress that would shield him from the immeasurable pain of private life. This, above all else, was the meaning of his magic circle.

"It is a truth universally acknowledged," Jane Austen famously observed, "that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife." Moïse de Camondo was no exception, choosing a bride 12 years his junior, Irène Cahen d'Anvers. Immortalized in an 1880 portrait by Renoir, Irène—lithe and delicate, but impulsive—was the eldest daughter of one of Paris's wealthiest Jewish financiers, Louis Cahen d'Anvers, an early principal of the bank that later became Paribas.

Like the Camondos, the Cahen d'Anverses were passionate collectors of 18th-century objets d'art, not to mention the proud owners of a château outside Paris, which they always said was a love lair for Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour. On the surface, then, Moïse and Irène seemed a perfect match: They came from the same rarefied Jewish aristocracy, and their marriage would consolidate two immense fortunes. In reality it was a disaster. After giving birth to two children—Nissim in 1892 and Béatrice in 1894—Irène left her husband for the man who ran the Camondos' stables. In a rash decision that became a cause célèbre of the society pages, the young woman abandoned her family, her faith, and her world. Her parents largely disowned her, and Moïse, who retained custody of Nissim and Béatrice, limited her access to them. Neither of these actions swayed her decision, and judging from the records that survive, she never looked back.

In the end Irène would outlive them all, surviving the war with a new Italian surname in a villa in the south of France. In any case, she had said her goodbyes to her children decades before their deaths, in a letter dated March 1903. "In the end, my darlings, you know how much I love you! That if I sometimes scold you it's only for your benefit, because I want you to be wiser and better children than the others!" she wrote. "You know that you are and always will be my dear children… Be wise and calm and obedient, and especially respectful and kind to your father, who loves you as much and even more."

That was undeniably true, and Moïse, utterly humiliated by the divorce, devoted the rest of his life to ensuring that his children grew up in as solid and serene an environment as he could create. This might explain why, in the years following Irène's departure, he ordered the refashioning of the family's home on the Rue de Monceau into an entirely new space, a tabula rasa for a new family life. Although he never acknowledged his pain in his extensive correspondence, his letters from those years evince an aesthetic autocracy. Amid the devastating chaos of real life, the house provided Moïse with a project whose every detail he could control when he had little control over anything else.

If perfection eluded—and even taunted—Moïse in life, it would never escape him in the sanctuary of the new house. Hiring the famed architect René Sergent to create a reconstruction of Versailles's Petit Trianon, Moïse aspired to a platonic ideal of neoclassical beauty, and he stopped at nothing to achieve it. He obsessively arbitrated every aspect of the house-to-be, demanding that his architect draw—and redraw—plans based on whims, sometimes entirely focused on certain objects in his collection. The house's pièce de résistance, for instance, the Salon des Huet, had to be constructed in an unusual hexagonal shape to display seven panels by Jean-Baptiste Huet, the Rococo painter, to Moïse's satisfaction.

His demands went into much deeper detail than that. "Dear Mr. Sergent," he wrote in July 1911, "following our conversation this morning, I would like you to go visit M. Fabre, an antiques dealer on the Rue de Rennes, to see two lanterns. You will be very kind to take their measurements and to make two small models for said lanterns to hang in our model of the staircase." In January 1913 he wrote Sergent, of the same staircase, "As the two galleries were done in wood, it would be absolutely illogical to do this particular staircase, which brings them together, in different materials."

And in October 1913, just months after the family moved into the not yet finished house, Moïse's anxiety over detail reached an even more extreme level. He insisted on a seemingly crucial change at the last minute: "Dear Mr. Sergent, I have long talked with Bourdier on the subject of the gilding of the ramp," he wrote after a meeting with one of his decorators. "He insists that we will never arrive at a suitable result with the gold we have already used; we must, he says, use LEMON GOLD and a skating by a man absolutely of the trade." The emphasis was his own.

Jewishness, for Moïse de Camondo, was a question not so much of religion as of community, a primary line of defense against an unforgiving and even hostile world.

But Moïse could not control everything, and his perfect world began to crumble from the inside yet again. As it was for many people in his milieu, Jewishness for Moïse de Camondo was a question not so much of religion as of community, a primary line of defense against an unforgiving and even hostile world. In the France of the Dreyfus Affair, the anti-Semites hated Jews for their race, but progressives often hated the Jewish religion for what they perceived to be its antiquated affront to secular modernity.

As much as Moïse sought to demonstrate his fidelity to France and its heritage, it was always imperative, in his eyes, that he live in a decidedly Jewish world, a constellation of intermarried families for whom solidarity was survival.

This was why his divorce from Irène was particularly devastating, and why he expected his children to marry within the community, even though they had no substantive Jewish education whatsoever. Doing so would ensure not only the preservation of the Camondo name but also its ancient identity from generation to generation. Only Béatrice heeded this call; to Moïse's horror, Nissim followed his mother's disastrous example. His daughter married the very respectable Léon Reinach, a composer from another fabulously wealthy Jewish family, but Nissim, Moïse's pride and joy, fell madly in love with a Protestant nurse and planned to marry her after the war, a fact Moïse would learn only after the young man's death, in September 1917.

His son's death was the great trauma of Moïse's life, and it left him a broken man. For years Nissim had written his father and sister letters from the war, sweet notes that assured them, through mentions of people they knew or horses they loved to ride, that he was far from danger. In a 1914 letter he described for Béatrice the "pretty gray horse" of a French general. "Voilà, my old Bamboula," he wrote, using his nickname for his sister, "good news for you today, no?" In his letters to Moïse, Nissim always stressed his safety: "We are in an area excessively calm with regard to artillery," he wrote in 1915. "Goodbye, my dear Papa. Kisses to you and Béatrice. Nine."

On September 5, 1917, Nissim de Camondo was in an airplane that went down somewhere over Lorraine, behind enemy lines. Moïse was notified via telegram, which at first he refused to believe. Weeks later he was still in the throes of magical thinking, entertaining the possibility that his son might return. But it was not to be. Worse, despite repeated entreaties to the French military, Moïse could not recover his son's body until after the war: Nissim had essentially vanished. If the young man's memory would be a blessing, it would also become something of a fiction, an incorporeal absence haunting in its lack of fixity.

In response Moïse managed his grief by holding close the things in his collection, which could always be kept where they belonged. In the years that followed Nissim's death, he scarcely allowed any object to leave the Rue de Monceau or even to be photographed. "This painting is the only ornament in my office, where I live constantly," he wrote in 1925 to one curator, who had requested Geneviève Le Couteulx du Molay, his prized portrait by Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, for an exhibition. "And I cannot deprive myself of it for such a long period." The same was true of his beloved bust by Jean-Antoine Houdon. "It's the only decoration on the fireplace in my living room," he wrote to a different curator in 1928, rejecting yet another gallery request.

These pieces had their specific places in Moïse's house, but they were also all that could anchor a man otherwise adrift in grief and disbelief. In May 1935, just six months before he died, Moïse apologized to Herbert Winlock, then the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, for his refusal to send even a small portion of his collection across the Atlantic. "Considering my great age," he wrote, "it would be painful for me to separate so long from an object that is dear to me." Of course it would be. For a man who had lost his wife, his son, and his world, the objects were the only permanent presence, the only things in Moïse's life that never abandoned him. They were his solace, his strength.

In 1942, Béatrice de Camondo—the sole overseer of one of the most significant collections of 18th-century masterpieces ever amassed—was arrested in her sumptuous Paris apartment.

In the end there was far more to lose,although Moïse could never have imagined exactly how much. In 1942, Béatrice de Camondo—the sole overseer of one of the most significant collections of 18th-century masterpieces ever amassed—was arrested in her sumptuous Paris apartment. At the beginning of the German occupation the consummate socialite had somehow managed to avoid the fate of so many other French Jews, and she carried on in surreal splendor for more than a year while the local authorities deported thousands upon thousands to their deaths.

There were even reports that she was going horseback riding in the Bois de Boulogne well into 1942 accompanied by a German officer, an emissary of the same regime that would ultimately demand the liquidation of her vast fortune. By all accounts she did not think of herself as a Jew, or even in danger; she had abandoned her religion long before, and she came from a stratospheric elite that viewed catastrophe as something that befell other people. But catastrophe found her in the end: She was executed in a gas chamber at Auschwitz on January 4, 1945, just two weeks before Soviet forces liberated the camp.

The mansion on the Rue de Monceau and the collection survived, but the world of the Camondos did not. In the formulation of the historian Tony Judt, the Europe that before the Second World War was "an intricate, interwoven tapestry of overlapping languages, religions, communities, and nations" was "smashed into the dust" by 1945. And so was an entire generation of cosmopolitan Europeans, a firmament of millions in which the Camondos were merely one family.

In that sense, Moïse turned out to be right about the objects in his collection and the strange, inexplicable power they wielded. As fragile a they seemed, they were all that was solid in a universe that melted into air. Objects are not people, but in their inanimate bodies they suggest, and in their stillness they preserve.

This article originally appeared in the March 2017 issue of Town & Country.